One Token to rule them all - obtaining Global Admin in every Entra ID tenant via Actor tokens

While preparing for my Black Hat and DEF CON talks in July of this year, I found the most impactful Entra ID vulnerability that I will probably ever find. This vulnerability could have allowed me to compromise every Entra ID tenant in the world (except probably those in national cloud deployments1). If you are an Entra ID admin reading this, yes that means complete access to your tenant. The vulnerability consisted of two components: undocumented impersonation tokens, called “Actor tokens”, that Microsoft uses in their backend for service-to-service (S2S) communication. Additionally, there was a critical flaw in the (legacy) Azure AD Graph API that failed to properly validate the originating tenant, allowing these tokens to be used for cross-tenant access.

Effectively this means that with a token I requested in my lab tenant I could authenticate as any user, including Global Admins, in any other tenant. Because of the nature of these Actor tokens, they are not subject to security policies like Conditional Access, which means there was no setting that could have mitigated this for specific hardened tenants. Since the Azure AD Graph API is an older API for managing the core Azure AD / Entra ID service, access to this API could have been used to make any modification in the tenant that Global Admins can do, including taking over or creating new identities and granting them any permission in the tenant. With these compromised identities the access could also be extended to Microsoft 365 and Azure.

I reported this vulnerability the same day to the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC). Microsoft fixed this vulnerability on their side within days of the report being submitted and has rolled out further mitigations that block applications from requesting these Actor tokens for the Azure AD Graph API. Microsoft also issued CVE-2025-55241 for this vulnerability.

Impact

These tokens allowed full access to the Azure AD Graph API in any tenant. Requesting Actor tokens does not generate logs. Even if it did they would be generated in my tenant instead of in the victim tenant, which means there is no record of the existence of these tokens.

Furthermore, the Azure AD Graph API does not have API level logging. Its successor, the Microsoft Graph, does have this logging, but for the Azure AD Graph this telemetry source is still in a very limited preview and I’m not aware of any tenant that currently has this available. Since there is no API level logging, it means the following Entra ID data could be accessed without any traces:

- User information including all their personal details stored in Entra ID.

- Group and role information.

- Tenant settings and (Conditional Access) policies.

- Applications, Service Principals, and any application permission assignment.

- Device information and BitLocker keys synced to Entra ID.

This information could be accessed by impersonating a regular user in the victim tenant. If you want to know the full impact, my tool roadrecon uses the same API, if you run it then everything you find in the GUI of the tool could have been accessed and modified by an attacker abusing this flaw.

If a Global Admin was impersonated, it would also be possible to modify any of the above objects and settings. This would result in full tenant compromise with access to any service that uses Entra ID for authentication, such as SharePoint Online and Exchange Online. It would also provide full access to any resource hosted in Azure, since these resources are controlled from the tenant level and Global Admins can grant themselves rights on Azure subscriptions. Modifying objects in the tenant does (usually) result in audit logs being generated. That means that while theoretically all data in Microsoft 365 could have been compromised, doing anything other than reading the directory information would leave audit logs that could alert defenders, though without knowledge of the specific artifacts that modifications with these Actor tokens generate, it would appear as if a legitimate Global Admin performed the actions.

Based on Microsoft’s internal telemetry, they did not detect any abuse of this vulnerability. If you want to search for possible abuse artifacts in your own environment, a KQL detection is included at the end of this post.

Technical details

Actor tokens

Actor tokens are tokens that are issued by the “Access Control Service”. I don’t know the exact origins of this service, but it appears to be a legacy service that is used for authentication with SharePoint applications and also seems to be used by Microsoft internally. I came across this service while investigating hybrid Exchange setups. These hybrid setups used to provision a certificate credential on the Exchange Online Service Principal (SP) in the tenant, with which it can perform authentication. These hybrid attacks were the topic of some talks I did this summer, the slides are on the talks page. In this case the hybrid part is not relevant, as in my lab I could also have added a credential on the Exchange Online SP without the complete hybrid setup. Exchange is not the only app which can do this, but since I found this in Exchange we will keep talking about these tokens in the context of Exchange.

Exchange will request Actor tokens when it wants to communicate with other services on behalf of a user. The Actor token allows it to “act” as another user in the tenant when talking to Exchange Online, SharePoint and as it turns out the Azure AD Graph. The Actor token (a JSON Web Token / JWT) looks as follows when decoded:

{

"alg": "RS256",

"kid": "_jNwjeSnvTTK8XEdr5QUPkBRLLo",

"typ": "JWT",

"x5t": "_jNwjeSnvTTK8XEdr5QUPkBRLLo"

}

{

"aud": "00000002-0000-0000-c000-000000000000/graph.windows.net@6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc",

"exp": 1752593816,

"iat": 1752507116,

"identityprovider": "00000001-0000-0000-c000-000000000000@6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc",

"iss": "00000001-0000-0000-c000-000000000000@6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc",

"nameid": "00000002-0000-0ff1-ce00-000000000000@6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc",

"nbf": 1752507116,

"oid": "a761cbb2-fbb6-4c80-aa50-504962316eb2",

"rh": "1.AXQAj_KHYn9PIkOWUahpfY_hvAIAAAAAAAAAwAAAAAAAAACtAQB0AA.",

"sub": "a761cbb2-fbb6-4c80-aa50-504962316eb2",

"trustedfordelegation": "true",

"xms_spcu": "true"

}.[signature from Entra ID]

There are a few fields here that differ from regular Entra ID access tokens:

- The

audfield contains the GUID of the Azure AD Graph API, as well as the URLgraph.windows.netand the tenant it was issued to6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc. - The expiry is exactly 24 hours after the token was issued.

- The

isscontains the GUID of the Entra ID token service itself, called “Azure ESTS Service”, and again the tenant GUID where it was issued. - The token contains the claim

trustedfordelegation, which isTruein this case, meaning we can use this token to impersonate other identities. Many Microsoft apps could request such tokens. Non-Microsoft apps requesting an Actor token would receive a token with this field set toFalseinstead.

When using this Actor token, Exchange would embed this in an unsigned JWT that is then sent to the resource provider, in this case the Azure AD graph. In the rest of the blog I call these impersonation tokens since they are used to impersonate users.

{

"alg": "none",

"typ": "JWT"

}

{

"actortoken": "eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1Qi<snip>TxeLkNB8v2rWWMLGpaAaFJlhA",

"aud": "00000002-0000-0000-c000-000000000000/graph.windows.net@6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc",

"exp": 1756926566,

"iat": 1756926266,

"iss": "00000002-0000-0ff1-ce00-000000000000@6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc",

"nameid": "10032001E2CBE43B",

"nbf": 1756926266,

"nii": "urn:federation:MicrosoftOnline",

"sip": "doesnt@matter.com",

"smtp": "doesnt@matter.com",

"upn": "doesnt@matter.com"

}.[no signature]

The sip, smtp, upn fields are used when accessing resources in Exchange online or SharePoint, but are ignored when talking to the Azure AD Graph, which only cares about the nameid. This nameid originates from an attribute of the user that is called the netId on the Azure AD Graph. You will also see it reflected in tokens issued to users, in the puid claim, which stands for Passport UID. I believe these identifiers are an artifact from the original codebase which Microsoft used for its Microsoft Accounts (consumer accounts or MSA). They are still used in Entra ID, for example to map guest users to the original identity in their home tenant.

As I mentioned before, these impersonation tokens are not signed. That means that once Exchange has an Actor token, it can use the one Actor token to impersonate anyone against the target service it was requested for, for 24 hours. In my personal opinion, this whole Actor token design is something that never should have existed. It lacks almost every security control that you would want:

- There are no logs when Actor tokens are issued.

- Since these services can craft the unsigned impersonation tokens without talking to Entra ID, there are also no logs when they are created or used.

- They cannot be revoked within their 24 hours validity.

- They completely bypass any restrictions configured in Conditional Access.

- We have to rely on logging from the resource provider to even know these tokens were used in the tenant.

Microsoft uses these tokens to talk to other services in their backend, something that Microsoft calls service-to-service (S2S) communication. If one of these tokens leaks, it can be used to access all the data in an entire tenant without any useful telemetry or mitigation. In July of this year, Microsoft did publish a blog about removing these insecure legacy practices from their environment, but they do not provide any transparency about how many services still use these tokens.

The fatal flaw leading to cross-tenant compromise

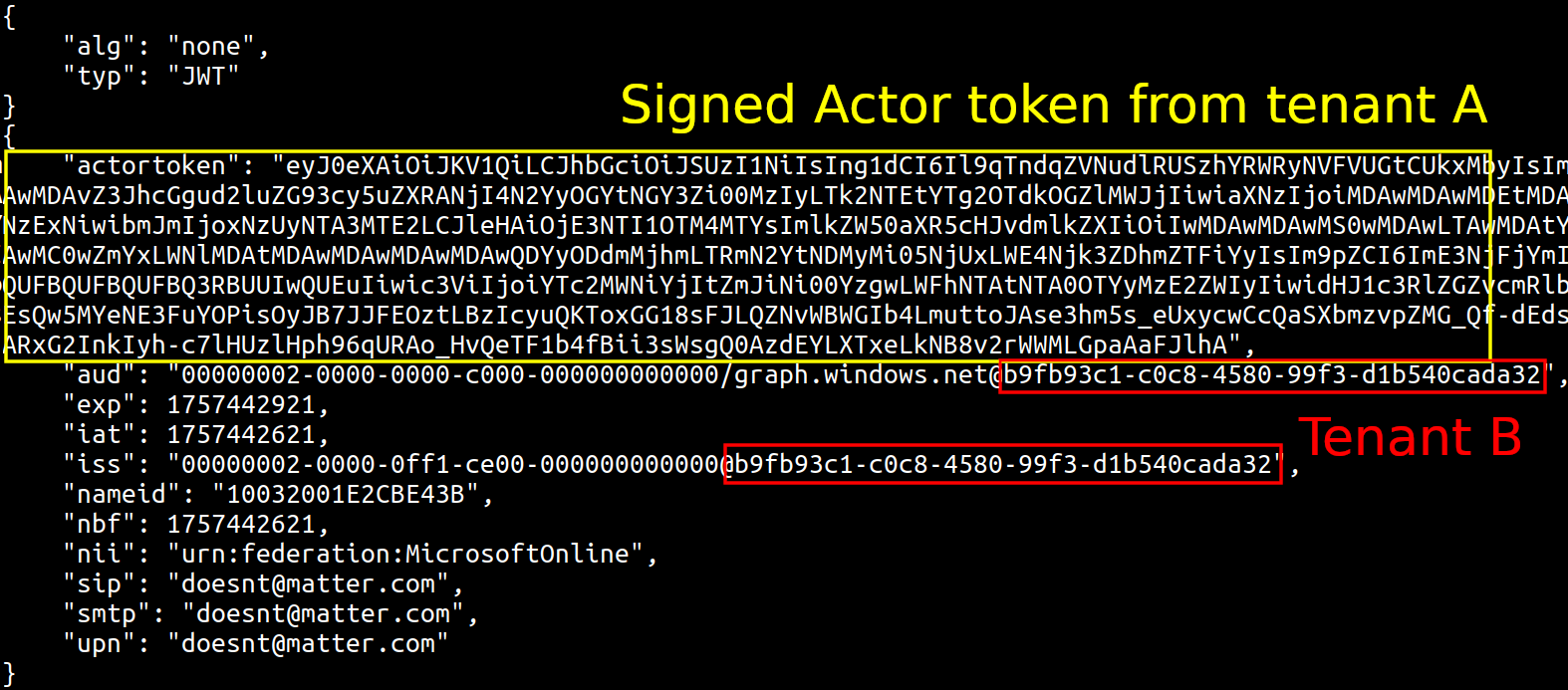

As I was refining my slide deck and polished up my proof-of-concept code for requesting and generating these tokens, I tested more variants of using these tokens, changing various fields to see if the tokens still worked with the modified information. As one of the tests I changed the tenant ID of the impersonation token to a different tenant in which none of my test accounts existed. The Actor tokens tenant ID was my iminyour.cloud tenant, with tenant ID 6287f28f-4f7f-4322-9651-a8697d8fe1bc and the unsigned JWT generated had the tenant ID b9fb93c1-c0c8-4580-99f3-d1b540cada32.

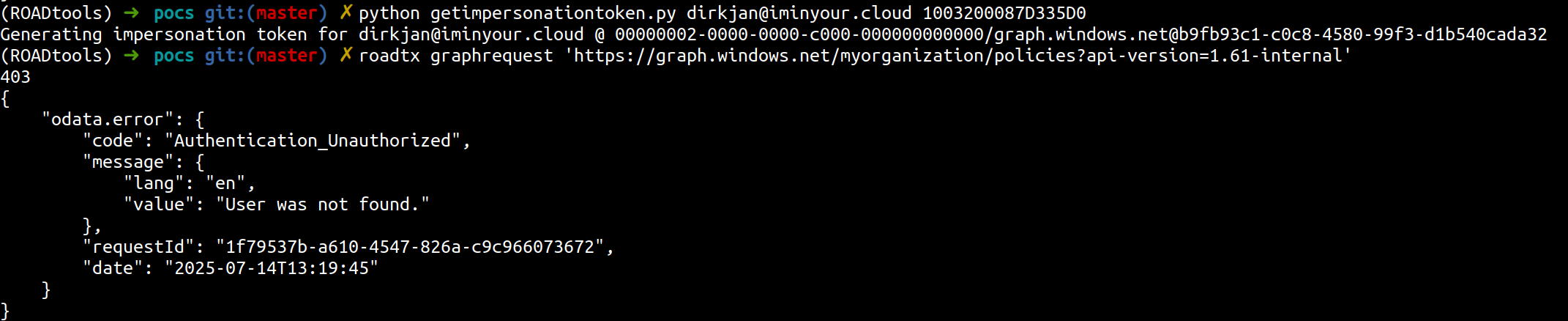

I sent this token to graph.windows.net using my CLI tool roadtx, expecting a generic access denied since I had a tenant ID mismatch. However, I was instead greeted by a curious error message:

Note that these are the actual screenshots I made during my research, which is why the formatting may not work as well in this blog

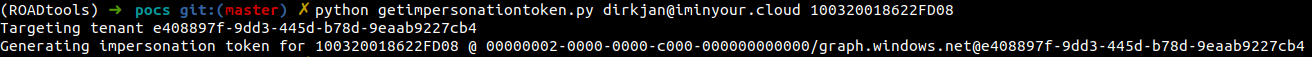

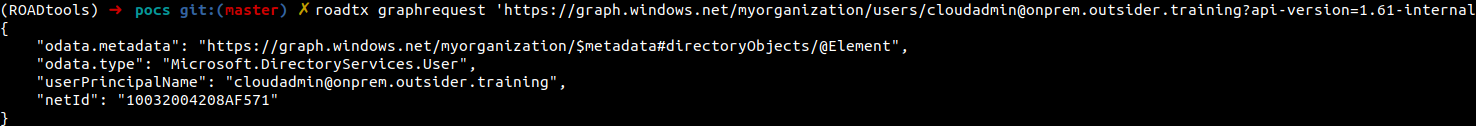

The error message suggested that while my token was valid, the identity could not be found in the tenant. Somehow the API seemed to accept my token even with the mismatching tenant. I quickly looked up the netId of a user that did exist in the target tenant, crafted a token and the Azure AD Graph happily returned the data I requested. I tested this in a few more test tenants I had access to, to make sure I was not crazy, but I could indeed access data in other tenants, as long as I knew their tenant ID (which is public information) and the netId of a user in that tenant.

To demonstrate the vulnerability, here I am using a Guest user in the target tenant to query the netId of a Global Admin. Then I impersonate the Global Admin using the same Actor token, and can perform any action in the tenant as that Global Admin over the Azure AD Graph.

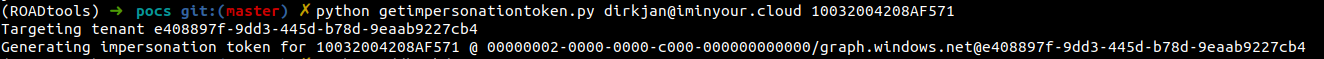

First I craft an impersonation token for a Guest user in my victim tenant:

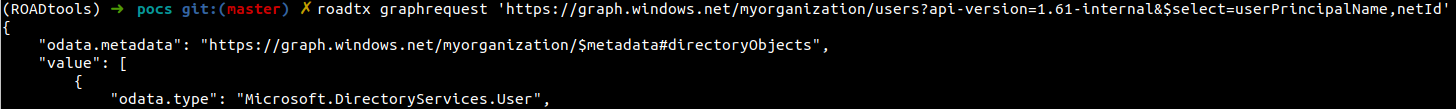

I use this token to query the netId of a Global Admin:

Then I create an impersonation token for this Global Admin (the UPN is kept the same since it is not validated by the API):

And finally this token is used to access the tenant as the Global Admin, listing the users, something the guest user was not able to do:

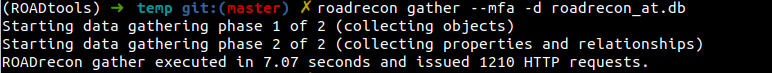

I can even run roadrecon with this impersonation token, which queries all Azure AD Graph API endpoints to enumerate the available information in the tenant.

None of these actions would generate any logs in the victim tenant.

Practical abuse

With this vulnerability it would be possible to compromise any Entra ID tenant. Starting with an Actor token from an attacker controlled tenant, the following steps would lead to full control over the victim tenant:

- Find the tenant ID for the victim tenant, this can be done using public APIs based on the domain name.

- Find a valid

netIdof a regular user in the tenant. Methods for this will be discussed below. - Craft an impersonation token with the Actor token from the attacker tenant, using the tenant ID and

netIdof the user in the victim tenant. - List all Global Admins in the tenant and their

netId. - Craft an impersonation token for the Global Admin account.

- Perform any read or write action over the Azure AD Graph API.

If an attacker makes any modifications in the tenant in step 6, that would be the only event in this chain that generates any telemetry in the victim tenant. An attacker could for example create new user accounts, grant these Global Admin privileges and then sign in interactively to any Entra ID, Microsoft 365 or third party application that integrates with the victim tenant. Alternatively they could add credentials on existing applications, grant these apps API permissions and use that to exfiltrate emails or files from Microsoft 365, a technique that is popular among threat actors. An attacker could also add credentials to Microsoft Service Principals in the victim tenant, several of which can request Actor tokens that allow impersonation against SharePoint or Exchange. For my DEF CON and Black Hat talks I made a demo video about using these Actor tokens to obtain Global Admin access. The video uses Actor tokens within a tenant, but the same technique could have been applied to any other tenant by abusing this vulnerability.

Finding netIds

Since tenant IDs can be resolved when the domain name of a tenant is known, the only identifier that is not immediately available to the attacker is a valid netId for a user in that specific tenant. As I mentioned above, these IDs are added to Entra ID access tokens as the puid claim. Any token found online, in screenshots, examples or logs, even those that are long expired or with an obfuscated signature, would provide an attacker with enough information to breach the tenant. Threat actors that still have old tokens for any tenant from previous breaches can immediately access those tenants again as long as the victim account still exists.

The above is probably not a very common occurrence. What is a more realistic attack is simply brute-forcing the netId. Unlike object IDs, which are randomly generated, netIds are actually incremental. Looking at the differences in netIds between my tenant and those of some tenants I analyzed, I found the difference between a newly created user in my tenant and their newest user to be in the range of 100.000 to 100 million. Simply brute forcing the netId could be accomplished in minutes to hours for any target tenant, and the more user exist in a tenant the easier it is to find a match. Since this does not generate any logs it isn’t a noisy attack either. Because of the possibility to brute force these netIds I would say this vulnerability could have been used to take over any tenant without any prerequisites. There is however a third technique which is even more effective (and more fun from a technical level).

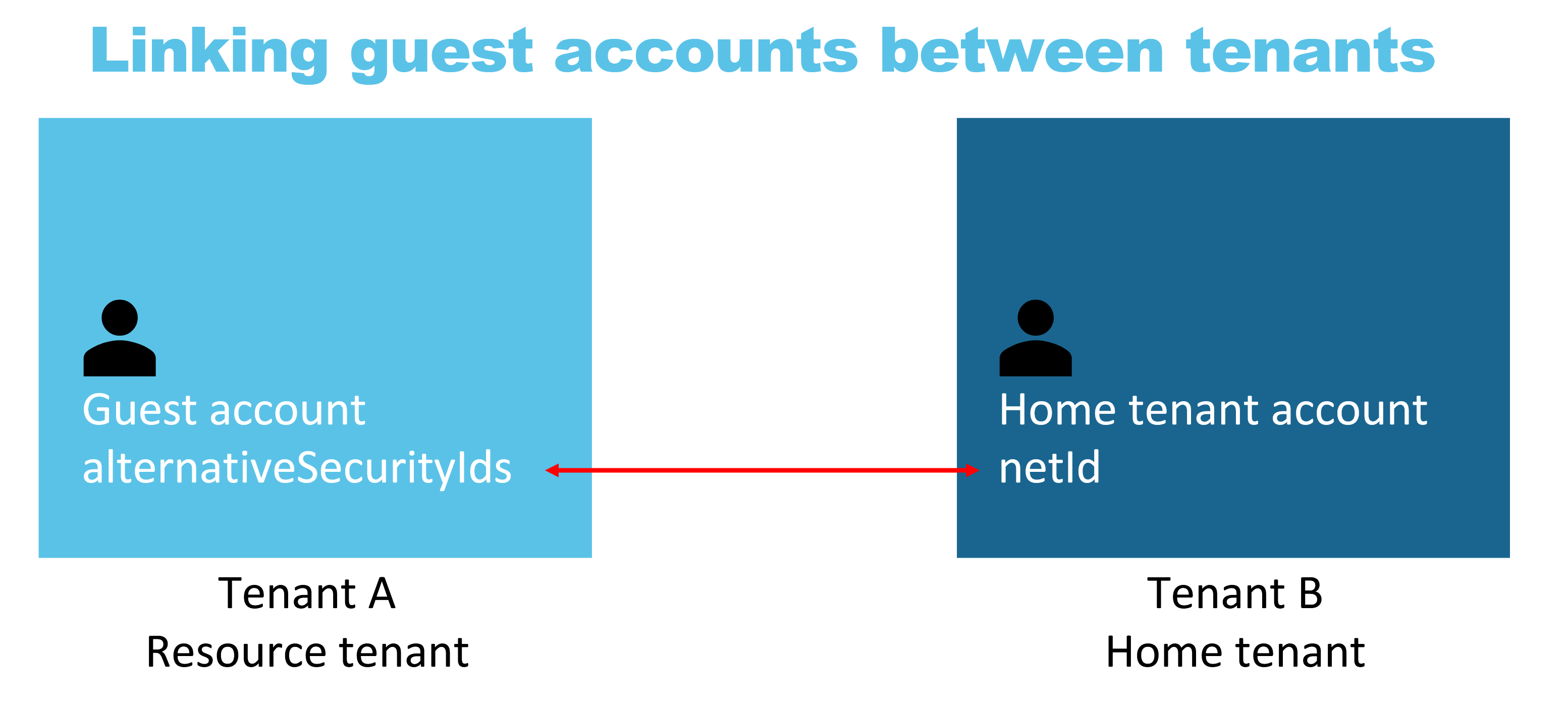

Compromising tenants by hopping over B2B trusts

I previously mentioned that a users netId is used to establish links between a user account in multiple tenants. This is something that I researched a few years ago when I gave a talk at Black Hat USA 22 about external identities. The below screenshot is taken from one of my slides, which illustrates this:

The way this works is as follows. Suppose we have tenant A and tenant B. A user in tenant B is invited into tenant A. In the new guest account that is created in tenant A, their netId is stored on the alternativeSecurityIds attribute. That means that an attacker wanting to abuse this bug can simply read that attribute in tenant A, put it in an impersonation token for tenant B and then impersonate the victim in their home tenant. It should be noted that this works against the direction of invite. Any user in any tenant where you accept an invite will be able to read your netId, and with this bug could have impersonated you in your home tenant. In your home tenant you have a full user account, which can enumerate other users. This is not a bug or risk with B2B trusts, but is simply an unintended consequence of the B2B design mechanism. A guest account in someone else’s tenant would also be sufficient with the default Entra ID guest settings because the default settings allow users to query the netId of a user as long as the UPN is known.

To abuse this, a threat actor could perform the following steps, given that they have access to at least one tenant with a guest user:

- Query the guest users and their

alternativeSecurityIdsattribute which gives thenetId. - Query the tenant ID of the guest users home tenant based on the domain name in their UPN.

- Create an impersonation token, impersonating the victim in their home tenant.

- Optionally list Global Admins and impersonate those to compromise the entire tenant.

- Repeat step 1 for each tenant that was compromised.

The steps above can be done in 2 API calls per tenant, which do not generate any logs. Most tenants will have guest users from multiple distinct other tenants. This means the number of tenants you compromise with this scales exponentially and the information needed to compromise the majority of all tenants worldwide could have been gathered within minutes using a single Actor token. After at least 1 user is known per victim tenant, the attacker can selectively perform post-compromise actions in these tenants by impersonating Global Admins.

Looking at the list of guest users in the tenants of some of my clients, this technique would be extremely powerful. I also observed that one of the first tenants you will likely compromise is Microsoft’s own tenant, since Microsoft consultants often get invited to customer tenants. Many MSPs and Microsoft Partners will have a guest account in the Microsoft tenant, so from the Microsoft tenant a compromise of most major service provider tenants is one step away.

Needless to say, as much as I would have liked to test this technique in practice to see how fast this would spread out, I only tested the individual steps in my own tenants and did not access any data I’m not authorized to.

Detection

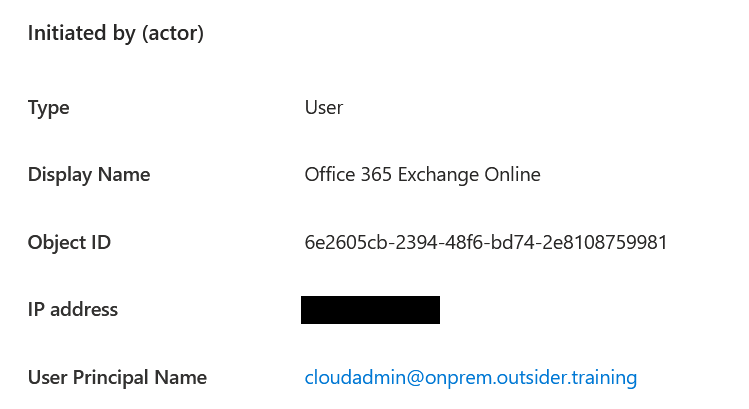

While querying data over the Azure AD Graph does not leave any logs, modifying data does (usually) generate audit logs. If modifications are done with Actor tokens, these logs look a bit curious.

Since Actor tokens involve both the app and the user being impersonated, it seems Entra ID gets confused about who actually made the change, and it will log the UPN of the impersonated Global Admin, but the display name of Exchange. Luckily for defenders this creates a nice giveaway when Actor tokens are used in the tenant. After some testing and filtering with some fellow researchers that work on the blue side (thanks to Fabian Bader and Olaf Hartong) we came up with the following detection query:

AuditLogs

| where not(OperationName has "group")

| where not(OperationName == "Set directory feature on tenant")

| where InitiatedBy has "user"

| where InitiatedBy.user.displayName has_any ( "Office 365 Exchange Online", "Skype for Business Online", "Dataverse", "Office 365 SharePoint Online", "Microsoft Dynamics ERP")

The exclusion for group operations is there because some of these products do actually use Actor tokens to perform operations on your behalf. For example creating specific groups via the Exchange Online PowerShell module will make Exchange use an Actor token on your behalf and create the group in Entra ID.

Conclusion

This blog discussed a critical token validation failure in the Azure AD Graph API. While the vulnerability itself was a bad oversight in the token handling, the whole concept of Actor tokens is a protocol that was designed to behave with all the properties mentioned in the paragraphs above. If it weren’t for the complete lack of security measures in these tokens, I don’t think such a big impact with such limited telemetry would have been possible.

Thanks to the people at MSRC who immediately picked up the vulnerability report, searched for potential variants in other resources, and to the engineers who followed up with fixes for the Azure AD Graph and blocked Actor tokens for the Azure AD Graph API requested with credentials stored on Service Principals, essentially restricting the usage of these Actor tokens to only Microsoft internal services.

Disclosure timeline

- July 14, 2025 - reported issue to MSRC.

- July 14, 2025 - MSRC case opened.

- July 15, 2025 - reported further details on the impact.

- July 15, 2025 - MSRC requested to halt further testing of this vulnerability.

- July 17, 2025 - Microsoft pushed a fix for the issue globally into production.

- July 23, 2025 - Issue confirmed as resolved by MSRC.

- August 6, 2025 - Further mitigations pushed out preventing Actor tokens being issued for the Azure AD Graph with SP credentials.

- September 4, 2025 - CVE-2025-55241 issued.

- September 17, 2025 - Release of this blogpost.

-

I do not have access to any tenants in a national cloud deployment, so I was not able to test whether the vulnerability existed there. Since national cloud deployments use their own token signing keys, it is unlikely that it would have been possible to execute this attack from a tenant in the public cloud to one of these national clouds. I do consider it likely that this attack would have worked across tenants in the same national cloud deployments, but that is speculation. ↩